Arizona Ash

August 31, 2022

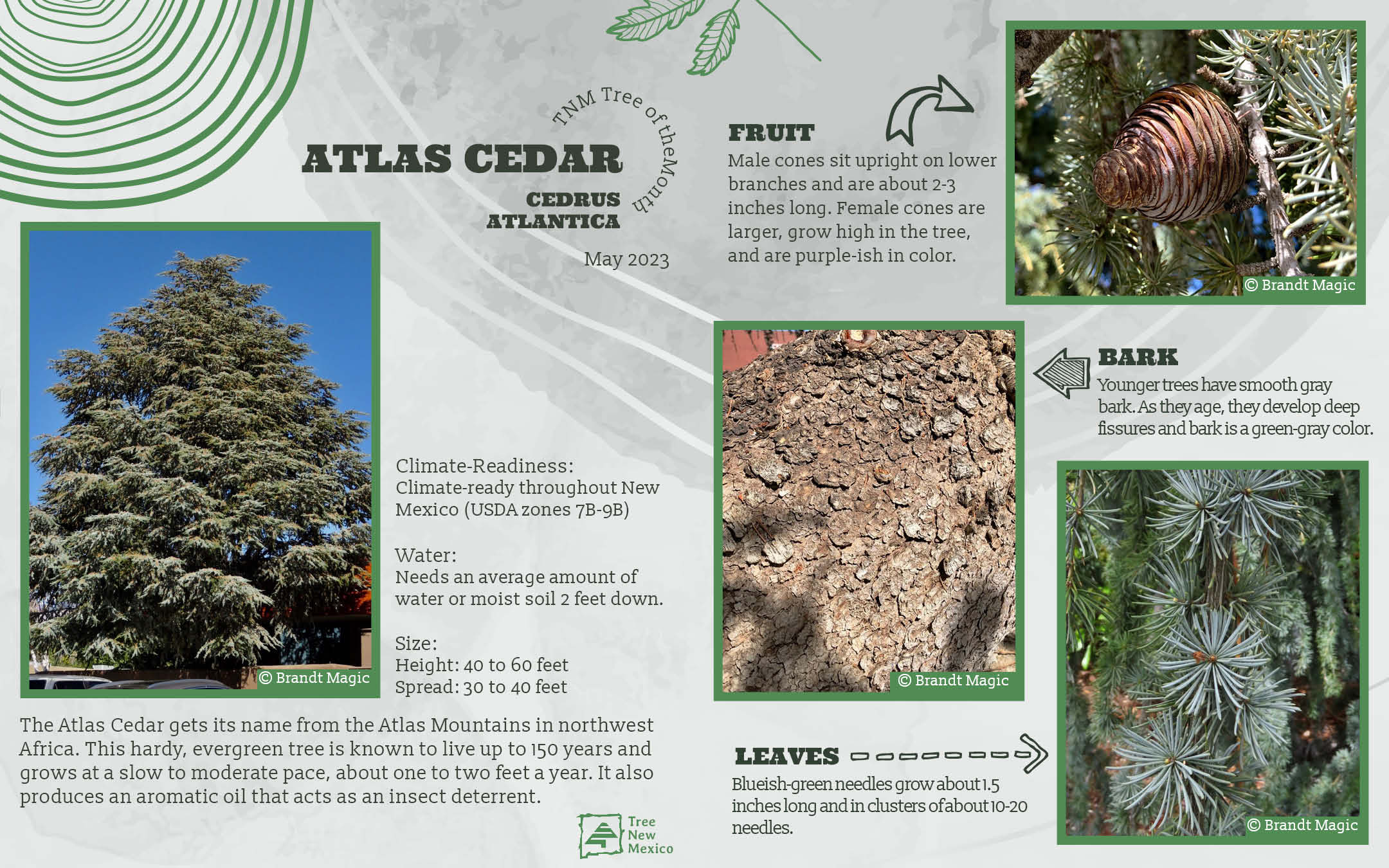

Netleaf Hackberry

September 7, 2022Bees and Trees that Please in New Mexico

Dr. Olivia Carril & Dr. Paul Polechla

In two of every three bites of food we take, we owe a debt of gratitude to “essential workers”, literally and figuratively. Bees, from before dawn until dusk, work to ferry pollen between similar flowers, discretely creating the seeds that will become next year’s flowers, and our tastiest fruits and vegetables. All for free.

As odd as it sounds, bees provide an avenue for most flowering plants to mate. Rooted to the ground as they are, plants rely on a match-maker to help them procreate. Pollen is the only portion of a plant that is truly male. It contains a random half of the DNA of a plant. When that pollen is deposited on the sticky stigma of another plant, it grows a tube, burrowing deep into the stigma and fusing with plant ovaries (eggs) at the base of the flower. The eggs, of course, contain the other random half of DNA needed to create a new plant.

Grasses like corn, rice, bamboo, and blue grama, bypass bees and other pollinators by letting pollen blow haphazardly from a tassel, catching the wind and counting on a bit of luck to get them to another plant, where it can become, for example, one kernel on an ear of corn. While this provides the carbohydrate staples of our human diet, it is the bees that allow for native cherries, raspberries, blueberries, service berries, elder berries, currants, and prickly pears. Without bees, there would be no apples, apricots, peaches, pears, pomegranates, brazil nuts, mangos, papayas, jujubes, tomatoes, chiles, onions, cilantro (their goes salsa), cantaloupes, strawberries, coffee, watermelons, broad beans, avocados, sunflowers, almonds, cranberries, pumpkins, alfalfa, or canola oil. Gone too would be the agaves that are used to make tequila. In the absence of bees, a rose by any other name would be… well, it wouldn’t be. Poets and romantics would have to look to the pines and the cycads for inspiration, since they, like grasses, are pollinated by the wind. The swell of spring fever that comes with the first blossoms of the year would wither.

Bees humbly provide the base of the food chain, providing not only for themselves, but for all organisms that rely on herbaceous material, fruits, or seeds (and indirectly for the ones that eat those herbivores). It behooves us to see them, to acknowledge in passing their hard work, to celebrate their diversity from time to time, and to offer them the minimal habitat that they require.

The European honey bee (Apis mellifera) is the bee that most people have in mind when they hear the word ‘bee’. They may cringe a little, associating their knowledge of bees with an unfortunate sting and having no desire to know any more about bees than that. However, the honey bee is a gateway, where knowledge of bees begins and not ends. In fact, most of the 20,000 bee species found in the world are nothing like the honey bee, and seldom sting.

Honeybees are incredible creatures with complex social organizations that rival others in the insect world, like their cousins the ants, and a far more distant relative, the human. Honey bees cooperate, dividing up the tasks required to maintain a colony of 30,000 individuals. One lone female (the queen) lays eggs, while the other females, all her daughters, divvy up the tasks of keeping the hive clean and functioning. Some act as nurses to growing offspring, some forage for nectar or pollen, some scout for better places to keep the hive, and some keep the hive clean and free of mites and other pathogens. They communicate their activities through complicated dances, eagerly and closely observed by their sisters, who pass the message on to those who weren’t around to see. There are also male bees, drones, produced by the queen when she deems the time right. Males fly away to other colonies and mate with young queens there. One mating event (often with 10 to 15 drones) provides her with enough sperm to last for the entirety of her seven-year life. As incredible as the honey bee is, however, they are poor representatives of the other 99.99% of bees found on Earth.

In the United States and Canada, it is estimated that there are nearly 4,000 bee species (with about 500 genera in the world); only one of them is a honey bee. The others are solitary, like Clint Eastwood in a spaghetti western. They work alone; each female builds her own nest, filling it with nurseries that will hold her eggs, each provisioned with a mound of pollen and nectar for her offspring. Most commonly these nests are in the ground, but they may also occur in rotting wood, hollow plant stems, snail shells, or divots in sandstone rock faces.

Unlike butterflies, birds, and beetles, bees prefer dry deserts. New Mexico, along with Texas, California, Arizona, and Utah have each over 1,000 species, fully 25% of what is known to occur north of the Mexican border. Scientists don’t know exactly why bee diversity is so high in deserts and other arid regions, but hypotheses include the longer flowering season, the quick turnover of flowering plants (each of which provides a new niche for a new bee guild), the lack of shadowy over story, and the dramatic elevational gradient found in most western states.

Here, we will celebrate the diversity of bees found in New Mexico, and a few found elsewhere, highlighting the biggest and smallest, the most dramatic looking, and those with the most interesting habits. We also highlight these bees from the standpoint of two bonus criteria: who they are named after, and how far and wide they occur. And the moral of our story is this: Please plant native New Mexico trees that please our native bees (and other pollinators).

Size, Body & Appendage

Wallace’s Giant Bee (Megachile pluto) (Smithsonian website) is the largest bee in the world, approximately 1 ½ inches long. It is named after Alfred Wallace, who co-developed the theory of evolution and advanced our understanding of biogeography immensely in his lifetime. The bee is found only in Indonesia, where it inhabits tree-dwelling termite nests. The bee has incredibly large jaws, presumed to be used to gather resin. Interestingly, the bee was thought to have gone extinct, but several sightings have occurred in the last five years that show that it is persisting even despite the extensive habitat fragmentation happening in the region.

The largest bee in New Mexico is a carpenter bee. Seldom seen north of Albuquerque, this gregarious bee is common in urban areas, and may inhabit trees and timber in backyards. The bee is one of the few that chews its own tunnels in wood, carving out a long gallery that subsequent generations will inhabit. Because the bees are so large, they don’t fit in narrow tubular flowers, and may be seen ‘nectar robbing’: cutting a hole at the base of the flower through which to pull nectar.

California Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa californica) on Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica).

Tiniest Fairy Bee (Perdita minima). The smallest bee in North America occurs in New Mexico, but only in the Chihuahuan desert, where it specializes on leafy spurge (Euphorbia sp.). The bee is about the size of the head of a pin.

The tiny fairy bee is one of 600 species in the genus Perdita, however. All are petite, though none as small as Perdita minima. Though most fairy bees fly during the late summer and fall, a few come out in the spring, including the Willow Fairy Bee (Perdita salicis), which only collects pollen from the catkins of Willows (Salix sp.).

As with bees in other groups, some species of these tiny fairy bees are very picky on the pollen that they feed to their offspring. Bees that preferentially collect pollen from only a few kinds of flowers, even when others are available, are called specialists. The pollen preferences of most bees, especially in this group, are not known. While scientists may hypothesize on the favorite plants of certain bees based on records of where they were collected, these are frequently changed as more information is collected. Thankfully, science is designed as to allow for self-correction if valid information refutes the old studies.

Fairy bee (Perdita sp.) on desert marigold (Baileya multiradiata).

The antennae of these male bees are exceedingly long, and have been observed to be used during mating to ‘calm’ the female. The male wraps his antennae around hers and gently strokes her antennae while they mate.

Mason bees nest in wood, and can be encouraged to nest in orchards. Their pollination services in these areas are unsurpassed. Two orchard bees have been shown to achieve the same amount of pollination as 100 honey bees. Orchard or Mason Bee (Osmia sp.) on native Rosaceae tree or shrub like American plum (Prunus americana) or chokecherry (Prunus serotina).

Bumble bees are among the largest and most charismatic of the bees found in New Mexico. Fuzzy, black and cheery yellow, plus slow enough that a mere human can watch them rummage through a flower, it is hard not to pause and observe their behavior. New Mexico has close to around 20 different species, and they can be distinguished by the colors of the hairs on various parts of their bodies.

Because bumble bees, with their fur coats, are able to fly when it is too chilly for other bees, they are common visitors of early blooming flowers, including many of our spring blooming trees. Hunt’s bumble bee (Bombus huntii). Photo by Joe Wilson.

Interestingly, bumble bees are the only native social bees in North America. Queens and her daughter workers maintain a hive that is started from a previous hive each year. Golden Northern bumble bee (Bombus fervidus) on thistle (Cirsium sp.).

American bumble bee (Bombus pensylvanicus) on Indian blanket flower (Gaillardia pulchella).

Morrison’s bumble bee (Bombus morrisoni) on Apache plume or póñil (Fallugia paradoxa) at Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona.

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/69927014 accessed 13 April 2021.

Cockerell’s Bumble bee (Bombus cockerelli) is the rarest bumble bee in New Mexico and the world, having been found only in one or two locations along the Rio Ruidoso in the last 100 years. This bee was named after T.D.A. Cockerell, an important entomologist in the early 1900’s. There is some ongoing controversy about whether this bee is its own species or should be relegated to a subspecies of something more common. As with many aspects of biology, research is ongoing.

Photo by: Matthew Kweskin

Dorsal view of a pinned, type specimen of Bombus cockerelli to document its existence. Photo by: Matthew Kweskin, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Department of Entomology USNM Number 56061, Barcode 00534350.

Green metallic sweat bees (Agapostemon sp.) are among the most commonly seen bees in New Mexico, and fly from late spring through to the first frost. Males are distinctive because of their yellow and black abdomens. Females, with few exceptions, are flashy green from head to tarsal tip.

Bees are interesting in that they are ‘haplodiploid’. Females mate, but store the sperm inside their bodies, rather than immediately fertilizing an egg. At the time that an egg is released from her body, she makes a choice about whether to release sperm as well. If she does, and the egg is fertilized, the new bee will become a female. If she lays an egg that is unfertilized, it becomes a male. In essence, her sons are half of her, genetically. Or put another way, her sons have a grandfather, but no father.

There are occasions where it appears that the fertilization isn’t complete, and gynandromorphs result. A gynandromorph is a hermaphroditic bee, and one half of the body will exhibit female characteristics, while the other half will look like a male bee. It occurs occasionally in bees, but the cause is unknown.

Texas striped sweat bee (Agapostemon texanus).

Behavior

The nesting behavior of cuckoo bees (Sphecodes sp.) are so sneaky that bee scientists give this devious yet adaptive behavior a special name; cleptoparasitsm. At least that is the case for the cuckoo bee. Specifically, cuckoo bee females lay their egg in nest of their host. When the larvae hatches, it kills the host bee, and then eats the pollen meant for it. They, like their bird namesake, the cuckoo (such as the common European cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) benefits from the spoils of the original host of the nest.

Interestingly, there are two birds in the cuckoo family here in New Mexico: the endangered western yellow billed cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus occidentalis) of the cottonwood bosque, and the New Mexico state bird, the roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus). However, they both are distant relatives of the European cuckoo and are not brood parasites like their “cousins over the pond”, or their bee namesakes. All three of the above cuckoo birds are alike in non-behavior characteristics.

Entomologist T.D.A. Cockerell named a new species of bee, Garcia’s Cuckoo Bee (Nomada garciana) after the famous, New Mexico horticulturalist Fabian Garcia. Professor Garcia became renowned for selectively hybridizing the chile Colorado, chile pasilla, and chile negro to develop the New Mexico No. 9 chile in the early 1900’s. This cultivar put New Mexico on the map and the now, world-wide chile industry was born. Mr. Garcia also studied the famous apple trees of Manzano, New Mexico and the pecan tree, later to become a major tree crop species in our state, with our production now rivaling the state of Georgia. Garcia also developed the Grano onion, from a Spanish cultivar In the early 1900’s. Regarding bees, Garcia collected the above-mentioned cuckoo bee in the agricultural fields of the “College Farm” of Mesilla, NM (now New Mexico State University) from the yellow sweet clover (Mellilotus indicus), an exotic legume.

The Fork-tailed Flower Bee (Anthophora furcata) buzz pollinates shrubs, like the point leaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos pungens), by landing on the flower and beating its wings so fast, that it creates a vibration, relinquishing the precious pollen from the tightly constructed urn-shaped flower.

Leaf cutter bees (Megachile) use pieces of leaves that they snip from flowers as ‘wallpaper’ in their nests, lining the inside of cells in old logs with the pieces to create envelopes that hold their offspring and the food their offspring need. There is some thought that the leaf choices made by the bees are related to medicinal or antifungal properties of the leaves.

Rio Grande cottonwood (Populus deltoides wislizenii) leaf cut by a leaf-cutter bee.

A male leaf cutter bee (Megachile sp.) on scarlet beehive cactus (Echinocereus coccineus), resting while he waits for a female to visit.

Wool Carder Bees (Anthidium sp.) are common in the summer and easy to recognize with their tiger-striped abdomens and hovering flight. While leaf-cutter bees take pieces of leaves and put them into nests, Anthidium pull trichomes (plant fuzz) from leaves and use it to ‘pad’ their nest cells.

Squash bees only visit Cucurbits when gathering pollen for their offspring. Males, which do not gather pollen nor help with nest construction, visit squash blossoms in hopes of catching a female there. They also sleep in the flowers at night. Squeezing a closed and wilted flower gently can be exciting (and harmless), as the bee inside will buzz, protesting the disturbance. The squash bee, buffalo gourd (a perennial vine) and squash, and extinct mastodon, and ancient Native Americans trace their history and coexistence back to 30,000 years ago. Squash Bee (Peponapis pruinosa) on buffalo gourd (Cucurbita foetidissima).

Female Diadasia sp. on caliche globe mallow (Sphaeralcea laxa), a sub-shrub. Her back legs look like saddle bags, loaded with the pollen that she has placed there to carry home to her nest.

Entrance to her ground nest.

Mining bee (Andrena sp.) on chokecherry tree (Prunus virginiana).

Two Colletid bees: Yarrow’s fork tongued bee (Caupolicana yarrowi) on white prairie clover (Dalea candida). a sub-shrub.

Halictid bees on three-lobed sumac (Rhus trilobata).

Hallictid bee on Emory’s seepwillow (Baccharis emoryi).

Female Megachilid on Emory’s seepwillow. Note the pale pollen-collecting hairs (scopa) beneath the abdomen.

New Mexico has long prided itself for its chiles, its salsa, and its fall festivals that celebrate the bounties of the harvest. A nod to the bees that visit our gardens, our wildflowers, are blossoming trees is also in order; worth celebrating, worth being proud of, and worth protecting. The Land of Enchantment includes more bee species than the 28 states east of the Mississippi River combined. These bees live around us, in the cracks in our sidewalks, the soil in our garden, yucca stems, and desiccating juniper trees. They are as in tune with the rhythms of our deserts as we are. Take a moment to look for these bees in your area. And encourage these fascinating and charismatic insects to take up residence in your back yard. Plant native New Mexico trees and shrubs that will ‘please our native bees’.

In central New Mexico, the following native New Mexico plants will attract native bees. Plant them!

NM native trees and shrubs:

-Peachleaf willow

-red willow

-Goodding’s willow

-Rio Grande cottonwood

-one seed juniper

-honey mesquite

-screwbean mesquite

-big tooth maple

-Rocky Mountain maple

-velvet ash

-net leaf hackberry

-Apache plume

-desert willow

-chokecherry

-American plum

-New Mexico locust

-Gambel’s oak

-black currant,

-golden currant

-chamisa

-three lobed sumac

-pale wolfberry

-broom dalea

-false indigo bush

-winterfat

-Great Plains seep willow

-Emory’s seep willow

-box elder

-NM olive

-western soapberry

-red barberry

-Wood’s rose

NM native vines;

-Arizona grape

-New Mexico hops

-trumpet creeper

NM native Cacti;

-Devil’s club cactus

-claret cup cactus

-scarlet beehive cactus

-Engelmann’s prickly pear

-Plains prickly pear

-desert Christmas cholla

-cane cholla

-walking stick cholla

NM native succulents;

-Parry’s agave

-soaptree yucca

-soapweed yucca

-beargrass

-desert sotol

-ocotillo

-banana yucca

For more information see:

Anonymous. (University of California – Riverside) December 6, 2011. “Scientists rediscover rarest U.S. bumblebee: Cockerell’s Bumblebee was last seen in the United States in 1956.” Science Daily. Accessed 7 April 2021. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/12/111205140616.htm>

Anonymous. JANUARY 6, 2017. Squash Bees and Mastodons. Native beeology: the unstung heroes. Accessed on 7 April 2021. https://nativebeeology.com/2017/01/06/squash-bees-and-mastodons/

Bosland, P. Fabian Garcia: Pioneer Hispanic horticulturalist. Chile Pepper Instituted, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM. Accessed on 15 April 2021. https://cpi.nmsu.edu/then-and-now/fabian-garcia/

Cockerell, T.D.A. 1907. New American bees. The Entomologist. Bulletin 40 No. 535.

Friese, H. (1911) https://www.aussiebee.com.au/aussiebeeonline004.pdf\

Grasswitz, T. and D. Dreesen. 2021 (Accessed on 7 April 2021). Pocket Guide to the Native Bees of New Mexico. New Mexico State University bulletin, Las Cruces, NM 30 pp.* https://aces.nmsu.edu/pubs/bees/welcome.html

Ruggiero M., Ascher J. & al. (2019). ITIS Bees: World Bee Checklist (version Sep 2009). In: Roskov Y., Ower G., Orrell T., Nicolson D., Bailly N., Kirk P.M., Bourgoin T., DeWalt R.E., Decock W., Nieukerken E. van, Zarucchi J., Penev L., eds. (2019). Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life, 2019 Annual Checklist. Digital resource at www.catalogueoflife.org/annual-checklist/2019. Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands. ISSN 2405-884X (fide Daniel P Cariveau).

Wilson, J. and O. M. Carril. 2016. The Bees in Your Backyard. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. 288 pp.